A Story of the Wives of the Waikato Missionaries

By Joyce Neill.

This is a tribute to the first European Ladies to make their homes in the Waikato. Most Church histories show the wives of the men who served them, as just a shadow behind their man; a few Maiden names are mentioned but their Christian names are often only known from their grave-stones.

After an uncomfortable, or even hazardous journey by ship from some other part of New Zealand, these people would arrive at the nearest little port; then usually they walked a Maori track inland. Sometimes they worked their way up the rivers, the highways of those days. At the appointed site, near some Maori pa, they gathered their few personal belongings about them and made a home.

Most of these gentle-women were from England, from homes where there were servants, and daughters were forbidden the kitchen area; when they arrived in New Zealand they learnt to cook over an open fire, for large numbers of people. They had also to do the most menial tasks for their families, without the simplest conveniences. The fear of fire was always in their thoughts, particularly while they lived in raupo-walled houses; so the cooking was done in a separate building.

Swishing to and fro to the “kitchen” in their long frocks, especially in the muddy winter-time, must have been a continuing aggravation.

Whether their men were attached to the Anglican Church Missionary Society, or to the Wesleyan Missionary Society of England, a comprehensive training for these women before they left for New Zealand, would have made a considerable difference. No attempt seems to have been made to give any medical service so even a better supply of medications would have been welcomed.

It is doubtful if many English mission ladies had a clear idea of the life they were expected to live here, or the full extent of their duties. Perhaps it was just as well they were left to learn them as they came along!

Apart from their practical work the missionaries relied on their wives for companionship. As a single man George Buttle, of the Wesleyan Mission, found life so unbearably lonely that he obtained permission to visit Australia in search of a wife. The journey was unsuccessful in spite of John Whiteley, his superior, giving his blessing to the enterprise.

Eventually, while completing some organising work in Auckland he married a Miss Jane Newman, a few months later they were transferred Te Kopua Station on the Waipa River, where she bore eight children before her death eleven years later.

THE MAORI PEOPLE. It is almost impossible for us, looking back from this time of great respect for the Maori people, to picture how they were living when the first white men came among them. From the extensive pa sites which have been discovered in the Waikato, it is evident that there was once a very large Maori population here. Writing of Northland, Judge Maning states his reasons for considering the immense numbers there had decreased by two-thirds during the last two generations before his arrival in 1833. He concluded this, not only from the size, number and closeness of these extensive pas, the number of men necessary to build and defend them, but also by the nearness of the hearth stones to each other at the hut sites within the pa’s. He considered the accepted form of cannibalism was the reason for the decimation; of course this genocidal trend hastened as they acquired guns. The same thing occurred in the Waikato.

Many of the Maori leaders saw what was happening and welcomed the “men of peace”; some chiefs changed and influenced their tribe when they accepted the Christian Faith; others, terrible fighting men, could not, although they encouraged the coming of the missionaries who brought education, agriculture, trade and prosperity, as well as the status symbol of owning a missionary. Most of the Waikato mission sites were selected by the tribes but without taking into account intertribal fighting and movements of population.

It transpired that several of them were badly chosen; the men and women finding themselves in the centre of a local war; or, as at Matamata (C.M.S), on a busy native track where war-parties frequently passed back and forth. There, cannibal feasts were not unusual – and very frightening.

It was at the end of 1834 that the Wesleyan missionaries arrived in the Waikato area and a few months later were making their way to an already chosen site. As they paddled up the Waihou River their canoe stopped at Puriri, near the C.M.S. Thames station, for Mrs. Stack’s time had come and her son was born there on the river bank; this baby was to become Canon James West Stack, well-known for his work at Kaiapoi.

When they moved on, Maori helpers carried the mother and babe in a litter-like amo made of vines and saplings. The haka welcome at each village frightened the young mother, especially as the Maori women, seeing their first white woman, would not leave her alone or give her privacy. They even touched her precious baby. Pretty Mary Stack, married at nineteen just before leaving England, had lived several months among Europeanised Maoris at the Bay of Islands. Now, with the Hamlins they were going to the new C.M.S. Station at Mangapouri, a large village at the junction of the Waipa and Puniu Rivers.

Here the excitable, untamed chief had recently murdered a relative; the wives, left on their own while Stack and Hamlin visited other villages had frightening experiences. Mr. Stack was home when the chief fired a gun, striking their house several times before a convert took away the weapon. One bullet went near where Mrs. Stack was sitting.

They closed the mission and moved to Matamata, where there was the same danger. The Hamlins were sent to open a station at Orua, Manukau Harbour, where the Stacks later joined them for a few months before transferring to Tauranga and Gisbourne.

Mary Stack lived only until she was thirty-five but it was because of her husband’s broken health that they returned to England where she died a few years later. Sometime afterward Canon Stack wrote this tribute:

“I have often wondered since how my dear young mother, with her English training and English ideas, and small experience of the world, could endure the thought of living alone with her little children in the midst of a lawless people who possessed no regular form of government, and all whom within the seven previous years had taken part in cannibal feasts. Nothing to my mind proves so convincingly her possession of perfect trust in the overruling providence of God. She felt quite safe, because she believed she was in God’s keeping.”

While they were living in that insecure situation at Mangapouri the Hamlin’s first child was born, and possibly he was the first child of white parents born in the Waikato. Canon Brown conducted his wife from Tauranga to assist when Henry Martyn Hamlin was born in 1836.

A few bricks, a dying grapevine, a plaque and rows of trees are all that remains from two houses, a store shed, a jetty and a church that once stood for eighteen months of labour and danger. When the Anglicans began again it was Otawhao, further south. There is now no sign of the large Maori Pa at Mangapouri.

The Waipa River was a very important highway leading into the interior, connecting through to Raglan, Kawhia and south to the Mokau and Wanganui Rivers. The Wesleyan mission at Te Kopua upstream from the settlement now called Pirongia, was in a very strategic position; it played an important role from 1841 until well into the Maori War. Six months before they arrived at the Waipa Mr. and Mrs. Thomas Buddle had, with Mr. and Mrs. Ironside been wrecked just outside the Kawhia Harbour entrance. The Buddle’s infant daughter, and most of their possessions were saved with the help of the Maoris. The Buddles lived with the Wallis family at the Raglan mission while the position of the Waipa station was chosen amid difficulties.

Te Wherowhero would not allow them to settle at the first place selected, while at the second choice they had made a home before the Maoris discovered it was “rahi-tapu” and the Buddles were told to move to Te Kopua; they were allowed to wait until a house could be built. To get settled anywhere must have been a relief. Under the shadow of Mt. Kakepuku lived a large population; it was reported that 200 Maoris attended one of the services; the site of this mission is marked by a cairn. After the Buddles the work was continued by George and Jane Buttle, and later Alexander Reid contributed to the peace of the area until the nearness of the fighting made staying unsafe.

HOSPITALITY. There are many recorded stories of the hospitality of these Te Kopua missionaries to others walking the Maori tracks. When Mr. H.H. Turton made an exploratory journey south, hoping to find a more suitable situation for the Wesleyan Mokau mission, he brought his wife and child the difficult trip from their home on the north western side of Aotea Harbour, near the entrance; over to Raglan and up the Waitetuna River. From there they went across swamp and hill country to the Waipa River where they thankfully rested at Te Kopua until his return five weeks later; then the return journey had to be undertaken.

Having the company of other women must have been a great joy on these occasions but unexpected visitors occasionally posed problems. In Rev. Lush’s diary Alison Drummond found the account of how, when he arrived at Kaitokohe, Taupiri, ahead of his host who had invited him, Mrs. Ashwell had to explain to him that as she had four young Maunsell children staying unexpectedly with her for a week, the only place she could put a bed for Lush was in a “closet”. Luckily it proved to be a large cupboard-like room “with shelves loaded with medicine” – the mission dispensary!

It is easy to imagine the baking and scouring that went on at Te Kopua when in April 1840 Thomas Buddle received word that Governor Hobson would be visiting there during the week-end of the 17th. The Rev. G.I. Laurenson in “Te Hahi Weteriana” describes how Rev. Buddle, on invitation from Mr. Morgan, joined in receiving and preaching to Hobson and his party at Otawhao. After dealing with local problems with the chiefs the Governor discussed with the Anglican and Wesleyan missionaries “matters dealing with recent and forthcoming legislation bearing on Marriages conducted by Maori or Dissenting Ministers”.

After enjoying hospitality in Buddle’s house at Te Kopua, sharing in worship, and inspecting the station, Governor Hobson, whose health was deteriorating at this time, went on a visit to the other Wesleyan Stations at Aotea and Whaingaroa……

SADNESS. Beside the cairn at Te Kopua is the grave of Mrs. George Buttle (Jane Newman); in her late thirties she died there, at the bend of the Waipa, three days after the birth of her eighth child; the baby appears to have survived.

In the story of Mrs. Maria Morgan are many aspects of sadness. Some of it is told by a grave-stone behind old St. John’s Church, near where the Otawhao Mission House stood at the Anglican mission at Te Awamutu. This stone tells the anguish of a mother’s grief. One of their sons died of an obscure disease at three years; the baby born a month later lived only four months; and even their eldest son died at fourteen years of age. Before they moved the Rotorua mission from Mokoia Island a child had died and been buried there. They had moved because the sulphur fumes caused a deterioration in Mrs. Morgan’s health. Their next home, on the eastern shore of the lake was made unsafe by warring tribes so they were transferred to the Waikato.

When Kate Hadfield, with her husband Octavius and baby son, were travelling from Auckland to their home in Otaki, the first overland journey by a white woman, she was able to stay three days with her aunt, Maria Morgan. The older women seemed unable to let Kate “our of her sight” during this brief visit of a relative.

One writer remarks that these early missionaries were all “old before their time”; is it any wonder? The women were inspired by Faith; on occasions its reward would compensate for days of worry. An apparent coincidence once saved the lives of Mrs. Morgan and two of her children. They were all sick the day there were two Europeans in the congregation when Rev. Ashwell of Pepepe preached at Rotokauri Lake near Hamilton. The one was a doctor who agreed to walk down to attend the Morgans.

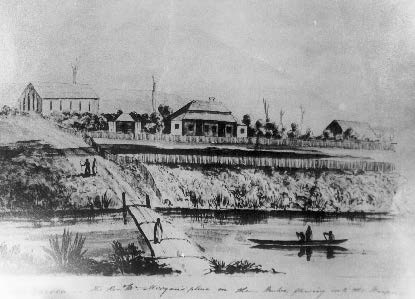

John and Maria had built up a very successful Government-subsidised school and fertile, picturesque farm there on the bank of the Mangahoe Stream. Nevertheless they left the Station in distressing circumstances after seeing the productive land neglected by the Maoris while they rushed from place to place attending “king” meetings. After being harassed by the Kihikihi Maoris, the unsettled times of 1861 caused the Government to send John Gorst as Resident Magistrate to the district to take over the mission property. Morgan felt he should have been consulted and resigned from the C.M.S. when the Church would not “protect his rights”.

DIFFICULTIES. In the early days Mrs. Maunsell at Maraetai Station, Waikato Heads, and Mrs. Ashwell at Pepepe near Ngaruawahia, (C.M.S. Stations) both lived much the same lives, feeding and caring for Maori and half caste children who lived at the school; as well as their own families. What difficulties there were in training the older Maori girls in the domestic arts – and managing their native servants!

Lack of “time sense” was the beginning of the trouble so when excitement occurred duties of any kind were forgotten immediately. A problem arose when the pa Maoris enjoyed their favourite foods and servants and pupils joined in the fun. Kaanga-wai, or maize kept moist until well-rotted “smelt worse than any drain”; while dried shark and dried turnips produced such an indescribably bad smell that all natives had to be ordered away from the house.

A different trouble was experienced by the Stacks when they had a frightening time with the irate husband of their nursemaid, who feared and hated him. Peace was restored when the Maoris induced him to swap Ani for some blankets and axes.

At Pepepe and Maraetai they had the worry of too many people for the food they could grow. In each case it was found advisable to re-establish where land was more fertile. The Maunsells moved to Te Kohanga a few miles upriver. Mrs. Maunsell died while still young and her grave is at Maraetai. The Ashwell’s moved down river a short distance to Kaitokohe, althought the boys’ school remained at Hopuhopu, over the river from Pepepe.

There were many times of tension there at Taupiri; the greatest was when a Maori was killed further north in Franklin district – by a pakeha, it was thought, and the Maoris were demanding the right to examine and punish. The Ashwell’s were alarmed when Wiremu Tamihana arrived with a war party of 300 men but he said that “Mr. Ashwell’s house and family were tapu and no one would dare to meddle with them.”

Mrs. James Wallis, like Mrs. Stack, was carried with her baby to her new home at Horea on the north side of Raglan Harbour. It had been a difficult journey from Kawhia so understandably she was delighted to arrive, although the raupo whare is reputed to have had then, neither doors nor windows. It would be well ventilated during the south-westerly gales!

Without any white women to assist, in fact twenty-six toilsome miles from the nearest mission house, her next baby was born there and Mrs. Whitely hurried from Kawhia, through swamp and bush, to help the household. When the Wallis’ returned to Raglan after a spell further north, they found the population had moved to Nihinihi across the harbour. Here the Wallis’ temporary shelter was a “four posted bedstead, roofed over with boards and blankets and had to answer the double purpose of drawing room and bed room. With as little delay as possible the Maoris erected a large raupo Church, one end of which they partitioned off as a temporary dwelling while a weatherboard house was being built”. This is how Rev. Laurenson quotes from Mr. Walli’s account of their home. Elsewhere he mentions that at this time in March they had all recently been ill with influenza.

DANGER. There was always danger; Mr. Wallis nearly lost his life off the coast in his small boat; Mrs. Ironside must have worried about her husband as he flitted back and forth across Cook Strait; until the Wairau incident brought them back, to work in Taranaki. In his book “Tainui” Mr. Kelly remarks that there was danger also from the rough white men who roamed the Waipa-Waikato river country. These mission women were often left alone with their children for days. Also there was always the embarrassment of naked men strolling into their homes; or, as Dr. Maunsell found, coming naked to Church.

The dangers for the missions became more real as the Maori Wars drew nearer, until one by one they closed. Cort Schnackenberg moved from the Mokau Mission to Kawhia and Aotea, taking charge of the coastal missions until they became unsafe; but Aotea continued its work well into the war.

LITTLE ANGELS ONLY LEFT. The saddest part of the story of these women is the number of babes they lost. Mrs. Ashwell bore a son and five daughters. The boy died when he was eleven, while Sarah and Mary were the only girls to survive to adulthood. In 1858, the young lady who became the wife of James West Stack (the baby born at Puriri) visited this mission and describes Mrs. Ashwell: “I wish I could have seen more of Mrs. Ashwell, for the little I did see of her made one deeply interested in the story of her life in New Zealand. She had passed, like all the Missionaries’ wives, through periods of great danger and privation which had left their mark upon her health. The death of her only boy, Benjamin, whom she had hoped to see some day engaged in the sacred work of the ministry, was a sad blow to her, and some lines (a poem) she gave me at parting afford touching proof of the depth of her sorrow and the chastened spirit in which it was borne.”

Kawhia and Whaingaroa (Raglan) were the busy ports of the Waikato and the ladies of the missions, Mesdames Whiteley, Woon and Wallis, were beset by similar problems. Mrs. Woon appears to have been the only mission wife with nursing experience – a course in a London Hospital made her assistance invaluable. Being frequently in demand she travelled long distances giving what help she could. It is sad to read that one of her own babies lived only six months; he starved while his mother was sick, at a time when they were all short of food. The tribes around them were too busy with arguments, and preparations for wars to produce the needed food.

A few years afterwards the Whiteley’s son died and was buried beside James Woon at Ahuahu, Kawhia.

At this large harbour missions were begun in several places before Whiteley settled on a permanent site which later renamed Te Waitere after him. From Kawhia he helped Mr. and Mrs. H. Hanson Turton establish another Wesleyan Station at Raoraokauere, Aotea Harbour, in 1840; Turton named the station “Beechamdale”. Mrs. Turton is reported to have stayed eight weeks with the Whiteleys; her husband lived in a tent while the house was being built. Later Turton successfully delivered their first child, although his relief was overshadowed by his irritation that such a situation should be necessary. In 1846 Mr. and Mrs. Gideon Smales took over that post but months later Smales reported that his wife was “still suffering severely” because of too many journeys in small ships. Previous to arriving Mary Anna Smales’ baby had died as the result of a dreadful voyage from Hokianga to Porirua; which had left both Mrs. Smales and the older child very ill. Mrs. Turton died soon after leaving the Waikato shortly after the birth of her fourth child.

Mary, Mary Anna, Maria, Susan, Jane and ………..the other names seem lost. We remember these women, sadly, by their graves, or the headstones above their little children.

In spite of danger, discomfort and sadness there were moments when the strain was eased by a little humour. One recorded incident occurred after the Matamata house was hurriedly evacuated, their most precious belongings sent down river to the Thames Mission. Mrs. Chapman from Rotorua who had taken refuge at Matamata, spent a very cold night with Mrs. Brown, Mr. and Mrs. Morgan and several native servant girls on the banks of the Waihou River; under a piece of canvas thrown over the bushes. Their small fire of damp wood did not penetrate the cold of a fog and they were not helped by the knowledge that marauding Maoris had captured the baggage canoe containing their treasures. They were taken to Puriri when rescued by two missionaries. They must have laughed with relief as much as amusement when Mr. Morgan returned from a luggage hunt and told how he met a rescue party of friendly Maoris led by Wiremu Tamihana – son of Te Waharoa. This young chief looked grotesque “marching before the rest, with the utmost consequence, his head and olive-coloured face being enveloped in a black silk bonnet belonging to a Mrs. Chapman, while a strip of coloured print, tied around his neck, formed the remainder of his apparel.”

A lonely grave under a White Pine tree with name-stones broken and nearly lost; a clump of arum lilies, a rambling old-fashioned rose, old fruit or acacia trees or a very old grape vine; even a patch of oxalis in a paddock; these are some of the signs that these ladies once lived nearby.

SOURCES

J.W. Stack, Early Maori Land Adventures.

Alison Drummond, Early Days in the Waikato; Vicesimus Lush.

Dick Craig, South of the Aukati Line.

Canon H.T. Purchas, The English Church in New Zealand (1914).

George L. Laurenson, Te Hani Weteriana.

H.C.M. Norris, Armed Settlers.

Leslie G. Kelly, Tainui.

- Maning, Old New Zealand

Barbara Mac Morran, Octavious Hadfield.

John Gorst, The Maori King.

The Ashwell Papers, (Letter from Mrs. James West Stack – nee Jones).

Te Mata. Aotea, R.T. Vernon and C.E. Buckridge.

MISSION STATIONS MENTIONED.

Church Missionary Society – Anglican:- Thames at Puriri; Matamata at Waharoa; Orua, Manukau Harbour; Mangapouri; Otawhao (called by the Maoris Te Awamutu); Pepepe, Hopuhopu, Kaitokohe, at Taupiri; Maraetai, Te Kohenga, at Waikato Heads; Tukupoko – a name sometimes given to a Taupiri site.

Wesleyan Missionary Society of England:- Te Kopua (sometimes called Waipa); Te Horea, Nihinihi, at Whangaroa (Raglan); Beechamdale at Aotea Harbour; Kawhia at Papakarewa, Waiharakeke, Ahuahu or Lemon Point (changed to Te Waitere. Raoraokauere Maori name for Aotea situation.

Journal of the Te Awamutu Historical Society, Vol. 9, No. 1, 1974