Te Hokioi was part of the printed propaganda battle that preceded, and prompted, the Waikato wars of the 1860s. It was used for several years to print a pro-Kingitanga newspaper called Te Hokioi e Rere Atu Na – or The Soaring War Bird. The newspaper is representative of a wider history of printing in New Zealand, which began when William Colenso set up his press at Paihia in 1835.

The Hokioi press is a considerable cast iron artefact, five feet tall and almost the same wide. It was manufactured In England by Hopkinson and Cope in the mid-1800s, and was later involved in a series of events pivotal to the Waikato Wars. The Austrian geologist, Dr F.R. von Hochstetter, surveyed the colony of New Zealand for nine months in the late 1850s. During the Waikato leg of his survey von Hochstetter met Hemara Te Rerehau of Ngāti Maniapoto and Wiremu Toetoe of Ngāti Apakura.

In recognition of their generous hospitality they were invited back to Europe in January 1859 as guests of the Austrian government. There they learned the printing trade and returned to New Zealand in May 1860 with a printing press as a gift from the Austrian Emperor Franz Josef.

The press was probably set up at the Hopuhopu mission station, close to Ngaruawahia, and the first issue of Te Hokioi e Rere Atu Na was printed in late 1861. Its principal writer, Patara Te Tuhi , was lauded for his witty prose, and for the early years of the 1860s he argued in print on behalf of the Kingitanga movement — often at the expense of the colonial government. In response, Governor Grey ordered that an opposing press and paper, Te Pihoihoi Mokemoke, be set up at Te Awamutu by John Gorst. After only four issues of the government paper it ceased abruptly. Rewi Maniapoto of Ngāti Maniapoto, confiscated the Pihoihoi press and its fifth issue. The government press – along with its editor – was shipped back to Auckland.

The Hokioi press continued to print until the invasion of the Waikato in June 1863, when it was shifted by waka to Te Kopua, near a Wesleyan mission station, for safekeeping. Although it reportedly fell into the river along the way, it was recovered intact. There is some confusion in the record over what happened to the press after it was moved. One account has it that the press was moved to Huntly after peace was made in 1881 and was used to print another Kingite paper, Te Paki a Matariki. However, archives indicate that this was printed by another press, so it seems that the Hokioi press, after its short but turbulent run, languished in a paddock near the Waipa River. As the land surrounding it was converted into a succession of farms the press served a variety of purposes: as a cooking-pot stand for the Searancke family and as a tobacco press by locals.

In 1886 a local man reportedly purchased all of the type to be sold on to Auckland printers— although it was later alleged that the type was melted down for bullets during the Waikato war. Whether or not this happened is debatable – from time to time the successive owners of the property would plow up pieces of type.

The press remained largely forgotten in its paddock near the Waipā River until 1935, when members of the Te Awamutu Historical Society traveled out to the farm, then owned by C. Washer, to inspect it. It was reported to be dilapidated, with several components missing and no sign of the typeset. A reclamation party returned later that year to load it onto a lorry, at which time Augie Swarbrick, then president of the Historical Society, remarked that the feat “clearly demonstrated that historical research is not a matter of mental effort only”. The press was moved to Te Awamutu and stored in the offices of the Waipa Post to await more permanent storage. Te Hokioi has been a part of the museum’s collection for 80 years.

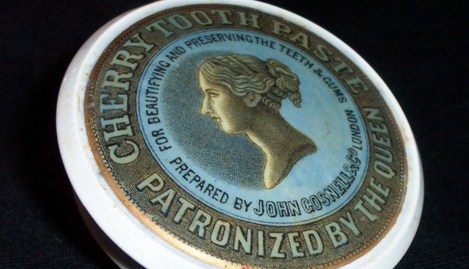

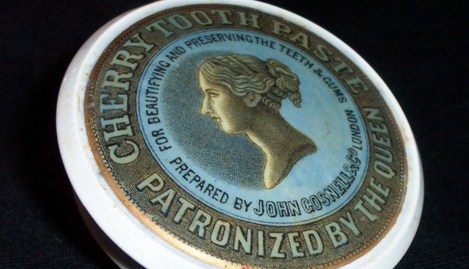

Toothpaste Pot Lid

This is a small porcelain lid of a toothpaste pot which was manufactured sometime around the mid 1880s or early 1890s by John Gosnell & Co of London. It was a popular brand of toothpaste until the First World War, and the company still exists today. The lid itself is ornate, with gold accents and a neo-classical bust of Queen Victoria – but thousands of such pots must have been manufactured and shipped to parts of what was then the British Empire. The cherry toothpaste and the lower half of the container have been used and discarded, but this lid helps us in part to understand how settlers established their lives in a new land.

This particular pot-lid was found on the site of the Kihikihi Redoubt by Richard Paul in the late 1970s and was later donated to the museum. The Kihikihi Redoubt was built during the Waikato Wars of the 1860s to strategically guard an important road into and out of the King Country. It was occupied by Imperial troops until the late 1860s when the Armed Constabulary took over. After an official peace was made with iwi in the early 1880s the site was used by the Police Department where they had a residence and a lock-up for a number of years. In 1984 an archaeological survey of the site commissioned by the Historic Places Trust unearthed a number of other objects. The report also concluded that the site had a very different use for a number of years as a strawberry patch.

If you want to research objects of a similar ages, try or collections online: https://collection.tamuseum.org.nz/objects?query=toothpaste+lid

By Pamela Langmuir

Often I used to stay with Grandma and Grandpa Langmuir in their grand home at the end of Laurie St overlooking the railway tracks. As it was school holidays my job at the Railway Tearooms was to ring a bell that was outside the shop to let the passengers off the train from Auckland for refreshments, to know where to come.

There was a coal range which had a large black kettle that had tea bags brewing. Those tea bags were my job too, making them with a square piece of linen – put in loose tea, tie with string and put in the kettle. Served with the best fresh ham sandwiches off the bone, ask any of the carriers or postmen who often stopped by. Grandma also made sultana cakes and long biscuits.

After, when the train was pulling out Grandpa would go through the train with his basket to collect any cups and saucers not returned – we didn’t want them to end up in Te Kuiti or Taumarunui. After the train pulled out my job was to empty the tea bags and wash the linen squares and string and hang them on the line to dry and get ready another lot for the next train. We never used the Railway toilets (no pull chain in the early years) but had our own commode in the back room surrounded by extra stock such as Sante Bars, Whitakers, Nestles Almond and Honey chocolates, cigarettes, etc. Handy place for light fingers!

On our way home after closing the Tearooms Grandpa would have his basket lined with newspaper and pick up the larger pieces of coal that had dropped from the rail wagons to keep the home fires burning.

With regard to Te Awamutu Railway cups and saucers not being returned, many years ago a farmer south of Te Kuiti was clearing gorse by the railway tracks and came across many cups and saucers, probably thrown out of the carriages when the passengers had finished.

If you want to see more images, research our collections online: https://collection.tamuseum.org.nz/objects?query=te+awamutu+railway+tearooms

Portrait of The Royal Family Queen Victoria, Prince Albert and their Five Children. Lithograph 1846

This lithograph is an exquisite exemplar of the reproduction of a portrait of the British imperial family. Franz Xavier Winterhalter, painter to the Royal Courts of Europe, completed this image in 1846. The Parisian lithographer, Alphonse Leon Noel, copied it on commission a year later.

Queen Victoria sits with the Royal Consort Prince Albert, surrounded by five of their nine children – on her right, Prince Alfred in white, and Edward the Prince of Wales in red, while daughters Princess Alice, and her first born, Victoria the Princess Royal, admire the infant Princess Helena. How did this remarkable picture find its way to Te Awamutu?

By 1849, the Waipā valley supported many flourishing flour mills, and vast acreages of grain. Early missionaries had introduced new horticultural practice and technology, in which the local iwi excelled. Their communities flourished, exporting produce to Auckland, and later Sydney and California. Three successful mills operated in Rangiaowhia, and entrepreneurial leaders included the chiefs Kingi (George) Te Waru of Ngāti Apakura and Hoani Papaiti (John Baptist) Kahawai of Ngāti Hinetu. When Governor Sir George Grey visited the Waipā district in 1849, these two chiefs urged him to present a gift of their finest flour, accompanied by a letter, to Queen Victoria. This missive declared –

“We, King George Te Waru, and John Baptist Kahawai, salute you; we return our thanks to you for your letter, in which you tell us that the land shall not be taken away; but that the Treaty of Waitangi shall be abided by. We are averse to fighting with white people, or amongst ourselves, but let the Queen always foster us; we approve of the custom of the white people, and the Governor loves us.”

As receipt of such gifts was not the Queen’s policy, the Secretary of State for the Colonies wrote from Downing Street, London on the 7th March 1850 acknowledging the above letter and the gift of flour to Her Majesty. Making an exception from her usual practice, the Secretary advised them that in this case she accepted both the flour and the letter –

“as an expression of their loyalty and attachment. As a mark of Her Majesty’s appreciation of the good conduct of these chiefs which you have reported to Her, the Queen has been pleased to order two pictures of Herself with His Royal Highness Prince Albert and the Royal children, to be transmitted to you for presentation to them”.

The two art works reached New Zealand in 1850. One was of the Royal Family; the other was described the Queen in ceremonial robes. They were exhibited initially in Auckland , as a “source of gratification to the native population generally”, and then conveyed by waka along the Mangapiko River, where they rested on the Sabbath, just below Ōtāwhao, now Te Awamutu. From there, they proceeded to Kahawai’s house, and then to the homestead of Te Waru.

At each place they were greeted with cheers and great excitement by both Europeans and Māori. In a letter dated December 12th 1850, the Reverend John Morgan noted that –

“the Queen arrived safely by waka at Rangiaohia on Monday the 9th, a little below the Rangiaohia mill”.

By referring to the paintings as a living person, the Queen Herself, Reverend Morgan reflects the Māori sensibility of the time. He eventually became the custodian of Te Waru’s gift, and his house was “frequently crowded with visitors looking at the picture for hours at a time…” Kahawai’s royal portrait was cared for by Father Garaval in the Roman Catholic Presbytery; Te Waru was a Protestant and Kahawai followed the Catholic faith.

In 1863, colonial forces invaded the Waikato. In February 1864, Randle Cotton Mainwaring, government agent, took possession of Morgan’s property which the Reverend had entrusted to Hohaia Ngahiwi, who was well aware of the importance of the painting. Mainwaring and his cohort occupied Ngahiwi’s house, and the mission, and then relocated Ngahiwi to Hopuhopu. He also took the painting to his own house at Whatawhata. From this point, conflict occurs. William Searancke, Resident Magistrate of Kirikiriroa (renamed Hamilton), acquired the artwork, insisting in private correspondence that “the picture was looted by the troops during the campaign and purchased by Mr Mainwaring from the soldiers. Hori Te Waru’s people then being in open rebellion.” Searancke thus acknowleged the image as a trophy of war, and effectively countered any further claims. The lithograph remained in his family for many decades.

Almost a century later, in 1958, Miss Phyllis von Sturmer donated the picture to the Te Awamutu Museum, “to be held in memory of my grandfather, Wm. Searancke.”

If you have any further information about the lithograph, contact our staff on 07 872 0085 or museum@waipadc.govt.nz

If you want to research our collections online: https://collection.tamuseum.org.nz/objects?query=lithograph

View the history of Waipa through the names of our streets.

Click on the blue tag to see the street name and who or what it’s named after.

View Waipa Street Names in a larger map

By Carly Daniels

You’re about to start the climb. Looking up to the top of the mountain, and it seems to grow. Grow higher and higher into the clouds. When you reach the top you look down. But you bend too far. You start to fall. You’re falling closer and closer to the ground. You can’t scream, then the second before you hit the ground you open your eyes. You’re at the bottom of the mountain. It was just a dream. Then you start the climb. this time you know not to look too far over the top.

Mt. Maungatautari is an amazing mountain full of beautiful birds and ginormous trees. It has a huge wall keeping out all unwelcome animals, aka pests. Some say that the mountain has two different halves, and if you look at it sideways left and right you can see the face of a man and the face of a woman. A lot of people like to climb up one side and climb down the other. This walk would take the average person 5-6 hours. On the bottom of one of the sides of the mountain there is a marae. This marae holds many stories of the mountain and the Maori culture that surrounds the mountain. The stories are from many years ago when the Maori families could not just go down to the shops to buy their food and drink. They had to retrieve it for themselves. Each story has a painting, each painting has the mountain in the background. Wether it is just sitting there or people are hunting in it, it is always there. Just hanging around.

Every day people all over the world are climbing mountains but very few get to experience the wonderful, beautiful scenery of Mt. Maungatautari. Some people say that you can see the two faces of the mountain because of the King and Queen of nature died and put their souls into the mountain that caused the mountain to form in the shape of their faces. Throughout the mountain there is a special plant that helps people when they are in pain. It’s like medicine. They used it before medicine came around. If you stuck part of one of the leaves on your tongue, tour tongue would go numb, causing the pain to stop. The Maori families would also mush up the leaves and use it as a liquid, so it could help with pain all around the body, not just in the mouth. So Mt. Maungatautari does not only have beauty, but it has great uses too.

Each person who climbs the beautiful mountain gets a great experience. The experience of a lifetime. I myself have been extremely lucky and I have been able to climb up the amazing mountain twice, and each time I learnt more and more about the mountain, and I enjoyed every second of it.

Want to research more about Maungatautari, check out our collections online: https://collection.tamuseum.org.nz/objects?query=maungatautari