By Ken Williamson

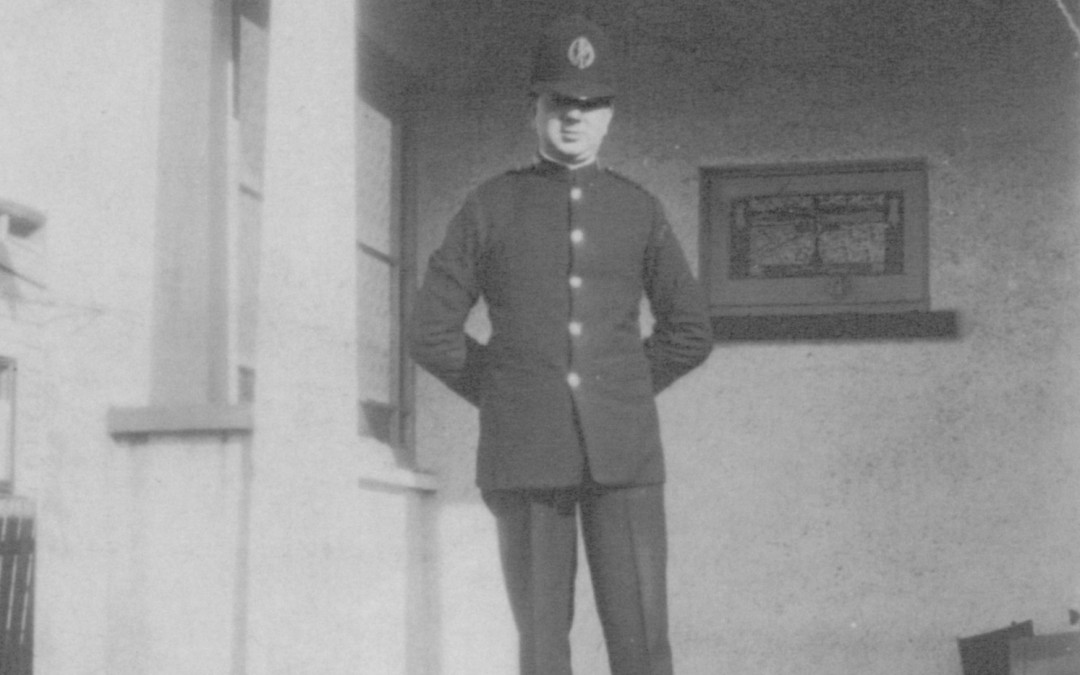

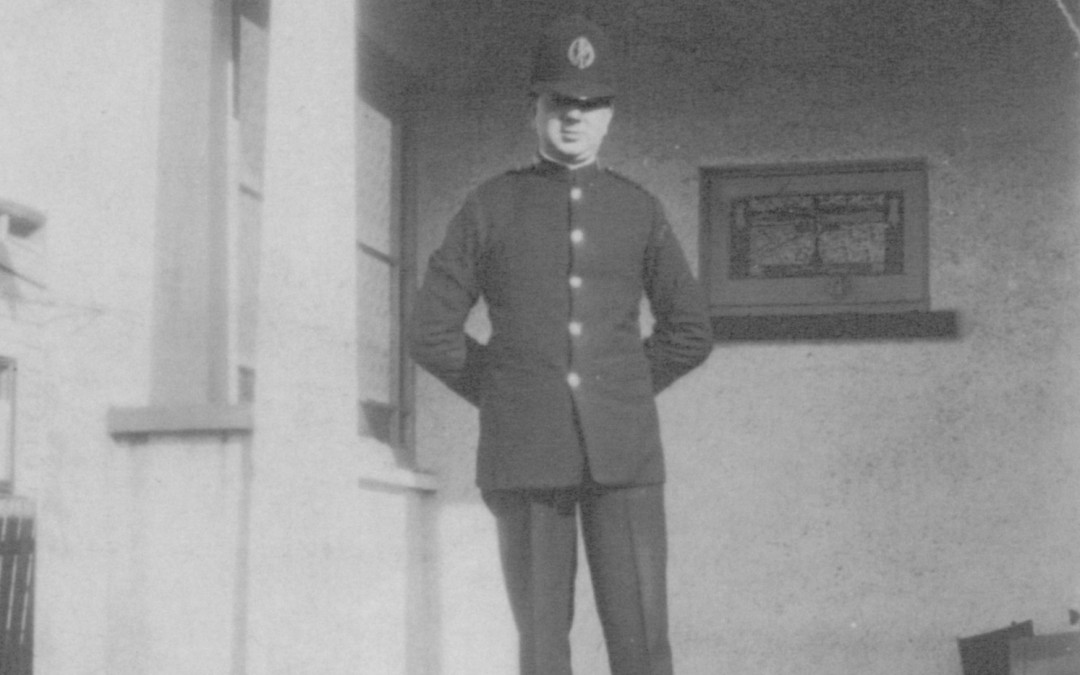

The Morning Shift – 5am to 1pm: One or two men would be put on fatigue at the city stations. Others would begin patrolling at what was a quiet time. Then the noise of tramcars and vehicles would begin with the rush of workers.

Breakfast was half an hour (in reality often no more than ten minutes to gulp down some food and tea) between 8 and 9am. By this time some of the men would be immersed in traffic control work.

During this period of time (1920-30) Point Duty was a routine part of the work of beat men on the main city thoroughfares between 8am and 6pm. Men on adjoining beats would spend alternate hours directing traffic. Genial greetings from regular travelers gave satisfaction, but point duty was tiresome.

It was while doing traffic control one morning that my father heard his school days nickname being called out. On turning around, he came face to face with one of his old classmates from England who was an officer on a ship that was berthed in Auckland. They were able to meet up later on in the day to catch up on each other’s news of the years since they had last met. He was able to meet my mother and her family.

Boredom controlling traffic soon set in if you did not take an interest in people, obtaining an occasional ‘Good Morning’ and getting to know the regulars on your beat, like the taxi drivers, city council workers, newspaper sellers and shopkeepers. Doing so meant they might drop hints on suspicious characters and provide assistance when needed. A cup of tea and a chance to rest could be offered at the back of a shop – but you still had to watch the clock and be at the fixed spot on time.

Want to research more about our constabulary? Try collections online: https://collection.tamuseum.org.nz/objects?query=constabulary&hasImages=true

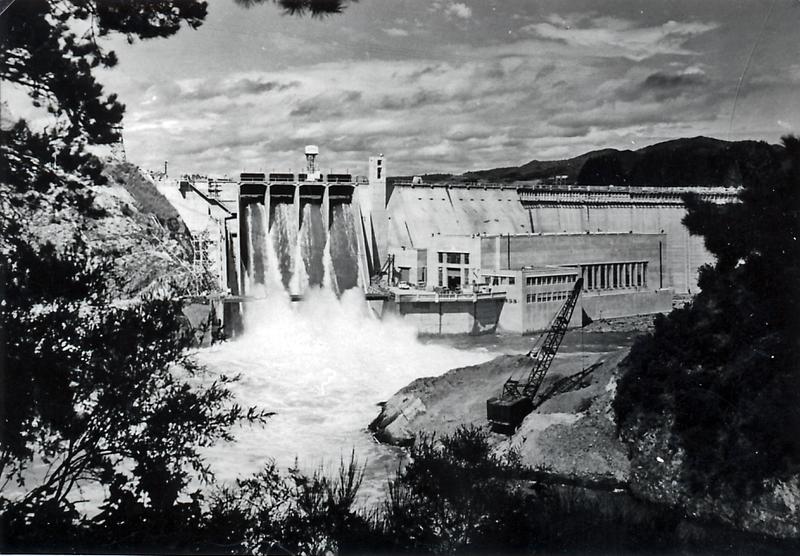

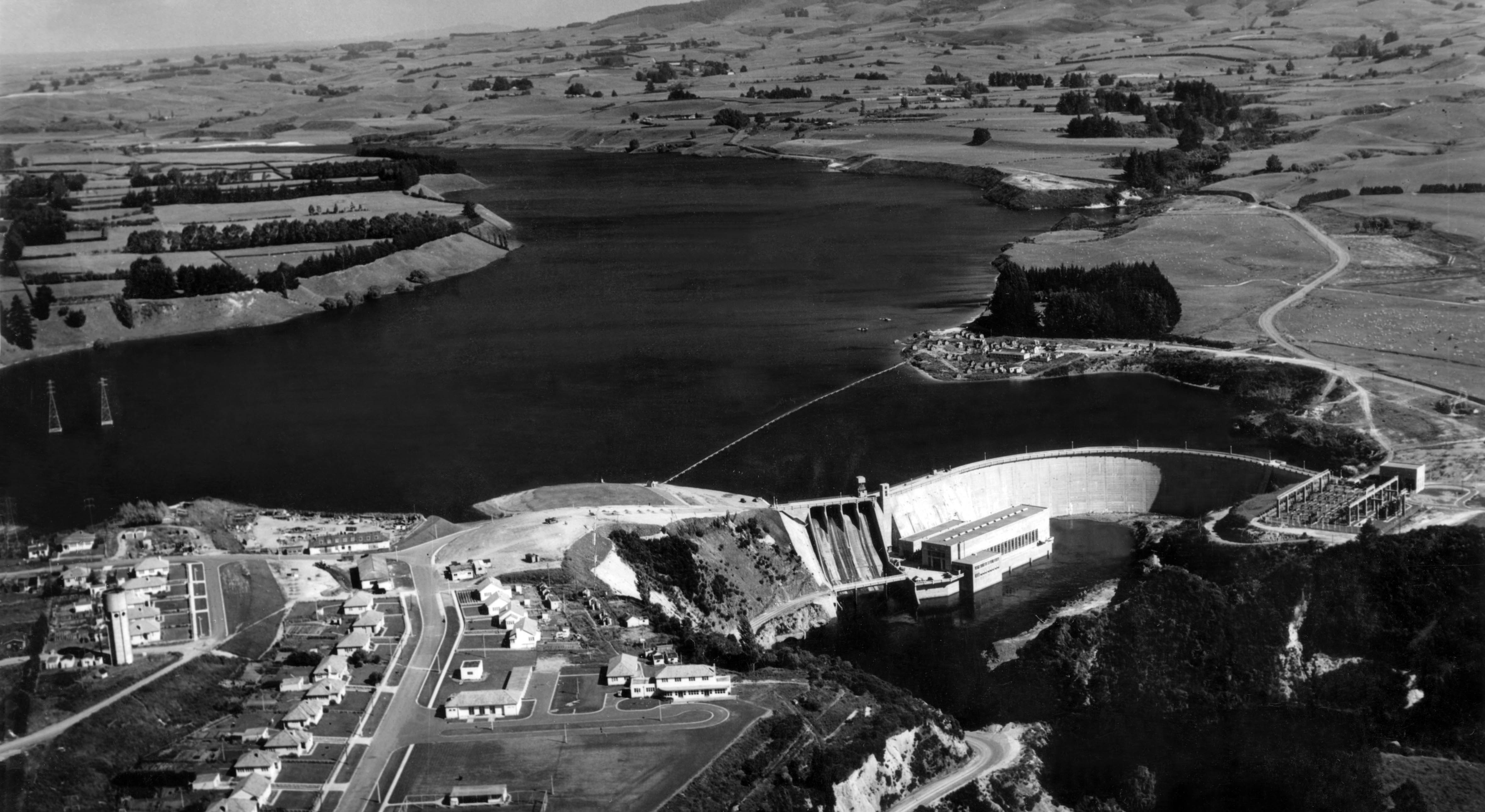

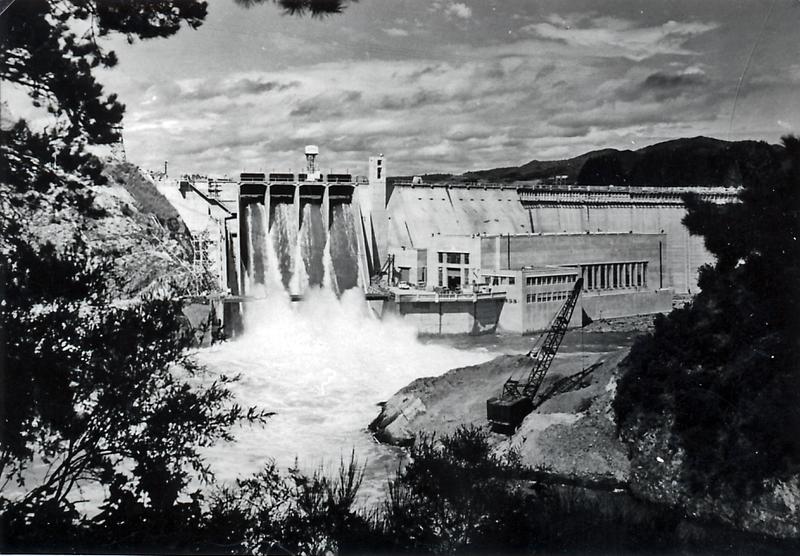

It was so quiet! There were no birds singing although the morning was sunny and warm.

Many people in the village had left with their families and furniture. Our belongings had already gone to our new home on Victoria Street in Hamilton. But today was the day the water would rise, and we were headed up the hill to watch it happen.

Mum had a large thermos with hot tea and a few sandwiches. My sister Dorothy and I looked at each other – we usually walked up this hill to our classroom in the Karapiro Hall but we’d be going to a school in Hamilton now, and Dad would be a mechanic at the Te Rapa Freezing works. People were gathered at the top, watching quietly as the water rose. “George, do you want a cup of tea?” asked Mum. “Yes please” he replied.

The ground and the roads were first to disappear, then the grass around the house, then the wood and the windows. Strangely we could see the reflections of the glass even through the water. The roof disappeared quite quickly, then the chimney; and then it was just a little history gone forever.

Dorothy and I each drew close to Mum and held her hand. Then we climbed into the truck and drove off to our new home in Hamilton.

By Jan Kilham

Florence had trained to be a missionary in China but was unable to go there. Instead she became the first sole-charge teacher at Piarere School, 1911 to 1913, living in a tent at the old creamery at the junction of the roads to Cambridge, Matamata and Tirau. About the same time, she was appointed as the Horahora Agent of the Presbyterian Church at Cambridge and she was able to use her Deaconess training to help the workers and residents of the Horahora Dam and village. It was a rough and isolated community with all the stresses that came with living and working there.

This lovely lady met a handsome young electrical engineer – Francis Charles Chase Smale, known to family and friends as “Charley”. Charley met with a serious accident on 11 October 1911 – he was crossing a live wire while carrying a drill that made contact with the wire. He received a shock of 5000 volts which burnt a large hole in one thigh and badly burnt his hands. Dr. Stapley came out to treat Charley then he was admitted to Waikato Hospital. After the doctors had done all they could, Florence took Charley out of hospital and nursed him herself. They were married on 9 October 1916.

In the wedding photo accompanying this story, Charley is seated – probably it would have been too hard for him to stand. The couple lived in Tauranga. Sadly,they didn’t have a long time together – Charley died less than a year later, on 29 August 1917, aged 29. Electricity is a marvellous yet dangerous tool.

Just one of our many archival wedding photographs in our collection. Want to view more? Go online to check out more images: https://collection.tamuseum.org.nz/objects?query=wedding&hasImages=true

Local boys make it big!

Brian Timothy Finn was born to Dick and Mary Finn at Te Awamutu on June 25, 1952. Brother Neil followed six years later. Both boys attended St Patrick’s School, situated at 625 Alexandra Street. The Finn family home was situated at 78 Teasdale Street, a building that is now a retirement home. The house is immortalised in the video for the Crowded House song Don’t Dream it’s Over. Father Dick was an avid jazz fan, and stories abound regarding the spirited parties held at the Teasdale Street house. By the age of 10 Brian was taking piano lessons from a local teacher. However, both brothers were musically inclined and would often perform at family gatherings and during holidays at Mt Maunganui.

In 1965 Brian started taking piano lessons with Te Awamutu jazz player Chuck Fowler, an experience that broadened his musical tastes and abilities dramatically. The following year, Brian moved to Auckland to attend Sacred Heart College and Auckland University, where he would meet many of his future bandmates.

Tim and Neil perform together

In the meantime, Neil remained at Te Awamutu, where he took piano lessons and taught himself guitar. He left Te Awamutu to attend Sacred Heart College in 1971, but left the following year and enrolled at Te Awamutu College (938 Alexandra Street). The college’s motto, Kia Kaha (forever strong), later served as the title of a song on the 1983 Split Enz album See Ya Round.

Neil became involved with a local folk group, All’n Some, and he and group member Felicity Saxby performed as a duo in various parts of Te Awamutu during the mid 1970s. In 1972 Brian, Mike Chunn, Rob Gillies, Geoff Chunn and Ben Miller won a talent quest at the Te Awamutu Racecourse. After leaving school, Neil Finn worked at a Te Awamutu record shop. He left in 1976 for London, where he would join up with brother Tim (having changed his name the previous year) and the other members of a group that was starting to attract a great deal of attention – Split Enz.

Please note a permanent exhibition is no longer on display, however some information is available by request at the Museum Front Desk.

Check out our collections online for more images: https://collection.tamuseum.org.nz/objects?query=split+enz&hasImages=true

Te Kooti Arikirangi Te Turuki

This kaitaka ngore once belonged to the Rongowhakaata leader Te Kooti Arikirangi Te Turuki (c1832 — 1893) who was variously known as a martyr, a rebel and a prophet during the New Zealand wars. Te Kooti was the founder of the Ringatu faith, which was based on interpretation of Old Testament text. Through this he was also the leader of a resistance movement against the colonial government. He was one of the most wanted men in the colony with a bounty of £5000 on his head until he was pardoned by a controversial act of parliament in February 1883.

The kaitaka and its story represent a complex and interesting period in the history of the region and of the nation. As an artefact of Maori-colonial interaction it is a treasure of significant value. From the quality of the weaving ¡t is clear that this kaitaka was made for a person of high status as it comprises a number of weaving styles. It features a bias well – or aho poka – which is a structural feature of the kaitaka, designed to give shape to the garment when worn and is decorated with thrums of black fibre tassels (huka huka) and woolen pom-poms (ngore).

The story of this kaitaka was re-told by local and overseas newspapers. The donor’s great-grandmother Mrs Hutchinson and her family lived on land opposite Orakau and near the Aukati line – behind which King Tawhiao had been exiled. Te Kooti camped nearby at Mangaorongo, between Kihikihi and Otorohonga. Given his reputation it is likely that many settlers would have felt uneasy about his presence in the district. Te Kooti and his entourage arrived one afternoon at the door of the Hutchinson house, and reportedly demanded food and drink — which Mrs Hutchinson provided. When she was asked by Te Kooti whether she was afraid of him, she said ‘no’, and in response Te Kooti gave her his kaitaka – and advised her that ‘so long as you wear this cloak no Maori will molest you’.

The kaitaka was taken to England by Mrs Hutchinson’s sister-in-law in, where it remained until 1954 when the donor, Mrs Peggy Wing, visited relatives and saw the garment herself. It was returned to New Zealand soon after and at Mrs Wing’s request underwent 75 hours of restoration.

Sources:

Judith Binney. Redemption Songs: A Life of Te Kooti Arikirangi Te Turuki. Auckland: Auckland University Press, 1995.

Ibid. “Māori Prophetic Movements – Ngā Poropiti – Te Kooti – Ringatū.” Te Ara – the Encyclopedia of New Zealand. Last modified June 25, 2013. http://www.TeAra.govt.nz/en/maori-prophetic-movements-nga-poropiti/page-3.

J.G. Graydon. “Te Kooti’s Korowai.” Journal of the Te Awamutu Historical Society 1, no.2 (1966): 43-45.

E.C. Hunwick. “Te Kooti Donatcd His Cloak as Protection for European Lady.” Footprints of History 17 (1996): 1-2.

Tainui Māori first settled the Waikato area as early as the twelfth century.

Their forebears sailed to New Zealand from Hawaiki. The Tainui canoe is said to be buried at Kawhia, and it was from there that the people consolidated and gradually spread, settling most of the Waikato and the King Country. It was a good area for settlement, with excellent growing conditions and river access. Many pā were established throughout, what we know as the Waipā, due to these favourable conditions.

From 1775 until approximately 1810 a number of prominent Waikato chiefs and warriors were born, including the first Māori King, Potatau Te Wherowhero of Ngāti Mahuta, Te Rauparaha of Ngāti Toa, Kawhia, and Hongi Hika, a Ngapuhi chief from the north, who played a significant role in Waikato history. It was Hongi Hika who invaded the Waipā triangle in 1822 at Matakitaki near Pirongia. The site of Matakitaki Pā was well suited to traditional Māori hand-to-hand combat, but the Pā’s inhabitants were defeated by the musket. This was the first time that European weaponry was used in the Waikato. The battle at Matakitaki was where the musket overcame the taiaha. Waikato leaders were quick to appreciate the value of the musket in battle, and traders soon appeared amongst the Maori people, trading muskets for flax. This was the first contact between Waikato Māori and Europeans.

The introduction of the musket resulted in a period of intense tribal warfare.

In 1834 missionaries visited the district, bringing changes to the Māori way of life. By the 1840s, after intervention from Wesleyan, Church of England and Catholic missionaries, there was peace. At Te Awamutu there were two important pa; Otawhao, a pā on the hill which is currently Wallace Terrace, and Kaipaka Pā, which is to be found at the end of what is now Christie Avenue. Otawhao, named after the Tainui tupuna (ancestor) Tawhiao, was first visited by missionaries in 1834. It was at Otawhao Pā that the first church was built in 1838, and where in 1839 Reverend Ashwell asked the Whare Kura (Christian Māori) to leave and set up a separate community at Te Awamutu. It was this act that led to the establishment of the Otawhao Mission Station. Morgan, who resided at the Otawhao Mission with his wife Maria from 1841 until 1863, made personal contributions to the history of the area were made in the areas of religion, education and agriculture. During this period there was a significant increase in Māori involvement in agriculture, including the establishment of a number of farms and flour mills, largely funded by Māori parishioners. The resulting produce and crops supplied, amongst other places, the Auckland markets.

During this period, at the request of the parishioners, permanent church buildings were erected; St John’s (1854) at Te Awamutu, and St Paul’s (1856) at Hairini (Rangiaowhia). The mission buildings were leased by the New Zealand Government in 1862, and John Gorst, as Civil Commissioner of the Waikato, took over the Otawhao Mission School. From within the mission site the printing press Te Pihoihoi Mokemoke began printing, in Maori, opinion opposing that of the King Movement newspaper Te Hokioi. In March 1863 Ngati Maniapoto seized the government press, and only after negotiation returned it onto the Queen’s land at Te Ia. This seizure was one of the many factors that led to the expulsion of Europeans from Te Awamutu and its districts, which in turn led to the outbreak of the Waikato Wars (1863-1865).

In 1864 the Otawhao Mission Station site became the headquarters of General Cameron’s army.

At the conclusion of the Waikato Wars ex-militia and settlers became the first Europeans to populate Te Awamutu. This was followed by the opening up of the area with the railway in 1880, and further development of the economy through farming, particularly dairying. The sale in 1907 of the Otawhao Mission Farm signalled the growth of the town of Te Awamutu.